Unlike the abundance of ‘soft’ documentaries to be found on satellite TV regarding marginalised and lost landscapes, Albert Lin’s professional credentials, combined with serious academic research, and use of high tech equipment sets his work apart from the majority of sensation-driven content that floods TV channels currently.

Here at AnMór Studio, Lin’s work has become something of a touchstone for inspiration, and a mine of information, as well as confirming a genuine groundswell of interest in marginalised landscapes that further demonstrates our hunger for understanding and revealing threads of our past that have been lost to time. It is genuinely gratifying to know that both in terms of content, quality and format, Lin’s work will help to engage a growing international audience in a broader, and deeper conversation about fragments of our lost past. With the help of his dedicated teams of researchers, combined with the very latest in cutting edge imaging, his work has shattered some of the assumptions that have been made around elements of past cultures, as well as encouraging historians and archaeologists, to rethink what was once enshrined in academic orthodoxy. His most recent expeditions are chronicled in the new NatGeo documentary series, Lost Cities Revealed with Albert Lin, premiering in December. The first episode, ”The Warrior King” follows Lin as he navigates a sacred mountain and a flooded tomb underneath a pyramid in the Sudanese desert, hunting for the lost capital of the Kingdom of Kush.

A California native, Lin holds a PhD in mechanical and aerospace engineering from the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). He subsequently founded UCSD’s Center for Human Frontiers, which focuses on harnessing technology to augment human potential. So it’s not surprising that he first made a name for himself by combining satellites, aerial remote sensing (drones), and Lidar mapping with more traditional ground exploration to hunt for the missing tomb of Genghis Khan in 2009.

The Valley of the Khans Project also successfully employed crowdsourcing (via more than 10,000 online volunteers) to help analyse the resulting satellite and aerial photography images, looking for unusual features across the vast landscape. That led to the confirmation of 55 archaeological sites in the region, a 2011 NatGeo documentary, and a 2014 scientific paper detailing the benefits of so-called “collective reasoning” to archaeology

Losing part of his leg didn’t keep Lin from continuing to pursue an active, exciting life, thanks to a high-tech prosthetic. He is still out in the field, searching for answers, while continuing to host numerous TV documentaries for National Geographic detailing his various expeditions, such as Lost Treasures of the Maya in 2018 and 2019’s Buried Secrets of the Bible. Lost Cities with Albert Lin debuted in 2019, featuring Lin’s efforts to locate the former headquarters of the Knights Templar in Acre, Israel, and the fabled city of El Dorado in the Columbian jungle, as well as exploring an archaeological site in the Peruvian Andes and the Black Mead mesolithic site near Stonehenge.

In addition to hunting for the lost capital of Kush, the latest series of Lost Cities documents Lin as he searches for an ancient lost Maya city that was once home to the people who built the great pyramid city of Palenque; visits the mountains of Peru to search for the lost Chachapoya kingdom that predated the Incas; visits Scotland to learn more about the lost kingdom of barbarian insurgents known as the Picts; searches in Israel for the lost city of the Canaanites; and hunts for a forgotten Bronze Age Arabian civilization (the Land of Magan) in Oman.

Needless to say, much of the content and ambition of Lin’s work resonates with the aims and intentions of AnMór Studio, and we hope in some small way to nurture a growing hunger for fresh interpretations and innovative ways to reveal the threads of our lost or forgotten past. In a recent interview, Lin discussed in depth, his motivation and gave some insight into how the newest branch of his work has given him a deeper understanding of our ancient past.

“This last season put us right at the edge of life and death multiple times, and yet it felt like there was a deeper purpose,” Lin says. “Every time we made a discovery, every time we found a body up high on the cliffs or the remains of some ancient city buried in the sands, it felt truly like we were on this important mission to try to unlock the secrets of who we are. So this is much more than a TV show for me.”

AT: Was it a different experience for you this time around, shooting another instalment of Lost Cities?

Albert Lin: There were a couple of things. One is that we’ve upped the ambition when it comes to the scale of things we’re searching for. That meant more time with the research and planning, more time with our technology out in the field. Let’s bring all the tools, whatever we can get. So we have a lot more Lidar, a lot more ground-penetrating radar, and a much bigger visualisation suite—how we re-create the worlds that we’ve scanned once we find them.

But on a more existential level, these six episodes, it feels like they’re more than just looking for footprints of cities or bricks of an ancient building. They seem to be tapping more into the deeper questions of how we organise ourselves in different civilisations. Each city is basically, in my mind, an experiment, a rise and fall, a chapter. In these six episodes, you really get a sense that each one of them reveals something about humanity, whether it’s about our resilience or about how we have succeeded when we’ve worked together with a globalisation approach, or what we’ve done in the past when we’ve worked together in non-hierarchical societies. It gets into a much deeper level of thinking for me.

You spend a whole career going off into far parts of the world, and you think somehow that maybe one day, it’ll all become normal. But this season, everything just was so intense and so real. The stakes were so high. We had so many moments where we almost almost died multiple times. We got lost in the river and a couple of guys almost drowned; we lost a lot of cameras; we got flash-bombed and tear-gassed, but the whole time it was like, we’ve got to keep going. It’s just felt so purpose-driven.

They took us out on these waters following these ancient glyphs inside the tomb of [Mayan ruler] Pakal, and sure enough, we found this massive mountain that “breathed” every time the wind and the lake system filled its belly with air. When we did all the Lidar scans, we realised that the whole mountain was terraformed into a massive pyramid. And when we descended into the heart of that mountain, we ended up finding all this pottery from the very earliest days of the Maya.

AT: I love the idea of a mountain breathing. Many people don’t realise that the entire Earth “breathes”—truly a living planet.

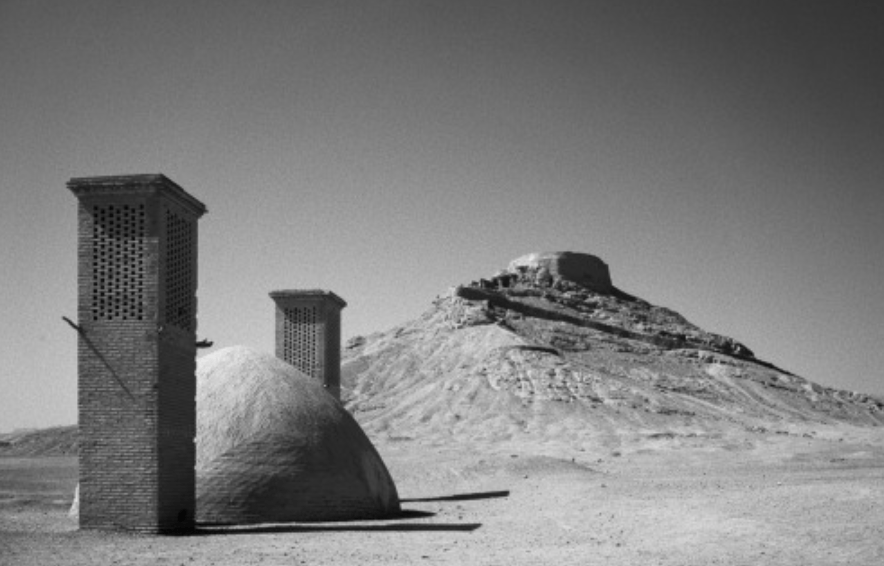

Albert Lin: I’ve seen how dynamic the natural world is, as well as the way in which humanity emerges from that dynamism. Being this close to the origin of the Maya, and then being in this jungle and seeing the whole breadth of their story, it really feels like I’m looking at one version of humanity, the one that comes out of the jungle. On another expedition, we were down in the deserts of Sudan along the Nile River. You’re in the heart of this ancient world that was erased from the history books by the people who came next, but you still see this deeply existential aspect of our humanity.

You find all these pyramids down there that are tied to some orientation of the sun, and you watch the sunset on top of a pyramid, and it lands right over the edge of this sacred mountain in the distance. You travel to the sacred mountain and find a temple to a moon, the Creator God, and then you find what might be a capital city. Looking at the sunrise and sunset across all these civilisations, it just reveals something about our humanity, these little magical bits that I feel like we’ve lost or we’ve forgotten. The journey that this has been for me, i’s just starting now to really reveal the depth of the story that’s emerging. What is humanity? I think that comes out more in this season.

AT: You’ve spent decades at this point getting a broad view of many different ancient cultures and civilisations. Perhaps you’re starting to see how it all links together, picking up on some universal truths about humanity and how we organise ourselves.

Albert Lin: You couldn’t have said it better. I’ve started marking this big wall poster in my office of all the timelines that I’ve bumped into. You see these emergent moments: here’s this technology that emerged or here’s this thing happened, and they seem disparate. But now, having encountered so many indigenous cultures, as well as the living descendants, you see these connections across all of them. It’s very humbling because it makes you feel like you’re part of a much bigger story. We’re, right now, on the final page that’s been written so far in this long history book of us. It feels like this universal human spirituality that exists across all cultures, and the struggles that we’ve always faced. We’ve been through mega 100-year-long droughts, we’ve dealt with the rise and fall of civilisations due to what was then considered global conflict. We’ve seen it all, we’ve done it all, and we’re continuing to do more. There’s just so many echoes. I feel like now, I’m starting to hear the echoes.

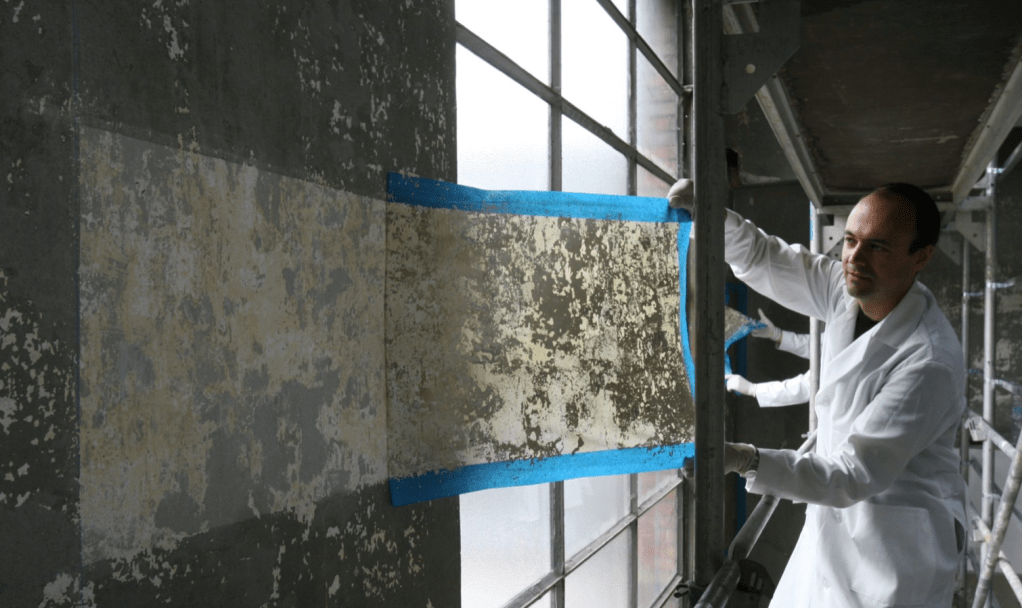

AT: You’re known for bringing cutting-edge tools such as Lidar to the field of archaeology. But you’re not just taking scans, you’re finding ways to re-create what things likely looked like, helping people who are not specialists get a very real sense of these civilisations.

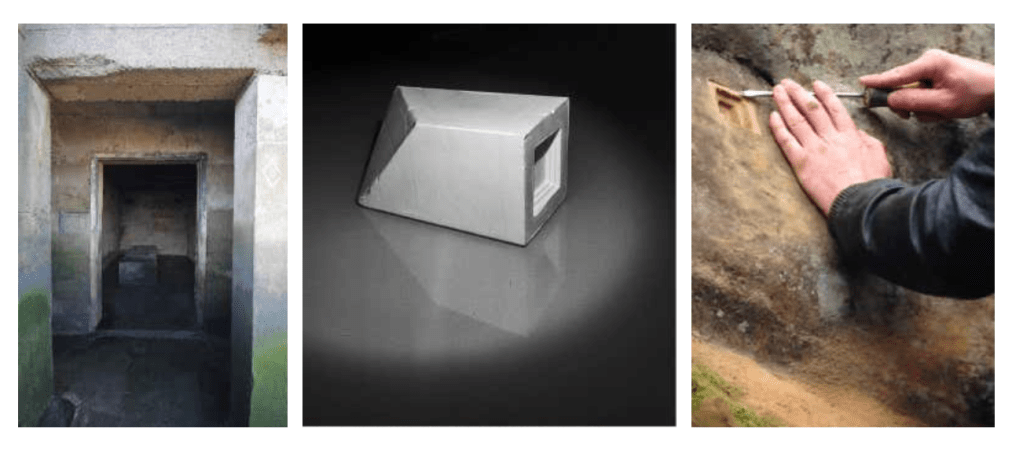

Albert Lin: I think of Lidar as a new tool that came on the scene, like the microscope or a telescope. It’s like, oh my gosh, now you can see everything, but you’ve still got to make sense of it all. For archeology, the first part is trying to see the hints with the Lidar, and then working with the archeologists who have dedicated their lives to interpreting the stones on the ground. We bushwhack in with machetes and snake gators and trowels. You end up getting down to the ground level, even picking up a piece of pottery.

You can tell certain things in the pottery, how old the site might be or the ways in which they created art. But then you put your hand across the thumbprint that’s in the pottery itself, and you feel the humanity locked in time, 2,000 years buried in the ground. You put yourself in the place of the person who placed it there, and you start to get a sense of why someone did that. It’s almost like you hear their poetry. It becomes so much deeper than some typographical model of the archeological site. It becomes this window into a shared humanity that expands your own being. All the technology we bring, it’s great. But the real thing I’m seeking is that feeling. We spent a lot more time in this new season with the VFX and the reconstructions to try and rebuild that ancient world in a way that makes you feel it.

We had this moment in the jungles of Mexico, early Maya stuff that has never really been seen before in terms of the style—these three-sided pyramids. You lay it all out on the map across this lake system and they’re all in some alignment. Why are they all pointed in this one direction? We modelled the course of the sun over different times of year through antiquity, but we couldn’t figure out the source of an alignment. On the very last day of the shoot, the lead archaeologist says, “Try August 15th.” We plugged it in and realised, oh my god, the whole thing is aligned to this one date on the calendar. August 15th is the origin day, it’s the first day of the Maya calendar. I found that wildly profound.

AT: What is next for you?

Albert Lin: That’s a good question. I think this last season was so intense that I am taking a minute to finish writing a book. I just spent a lot of time with a group of thinkers about the future of humanity and this divergent moment with AI. I feel like there’s answers to this existential moment that we face where we’re looking at cultural evolution and the evolution of technology. What is it that we’re afraid of losing? It’s because we sense that there’s some competition between the evolution of that thing, whatever it becomes, and the evolution of our culture. Then the question is, well, what is the essence of our culture? What is humanity? What is this thing that we’re afraid of losing?

I’m starting to see these broader connections across humanity. In my own body, I’m physically always feeling like I’m stepping one part in the future, one part in the past. I feel like the answers to these kinds of questions are tied to some of the earliest awakenings of our human consciousness. I’ve seen rock art all around the world that looks almost identical. I see symbolism in the ancient Maya that you see all over the world. It feels like if we’re going to worry about where we’re going, maybe it’s critical that we really understand where we came from at the origins.

The new season of Lost Cities Revealed with Albert Lin premieres on National Geographic Channel and is also available for streaming on Hulu/Disney+ on November 23, 2023. Interview sourced from Arstechnica.