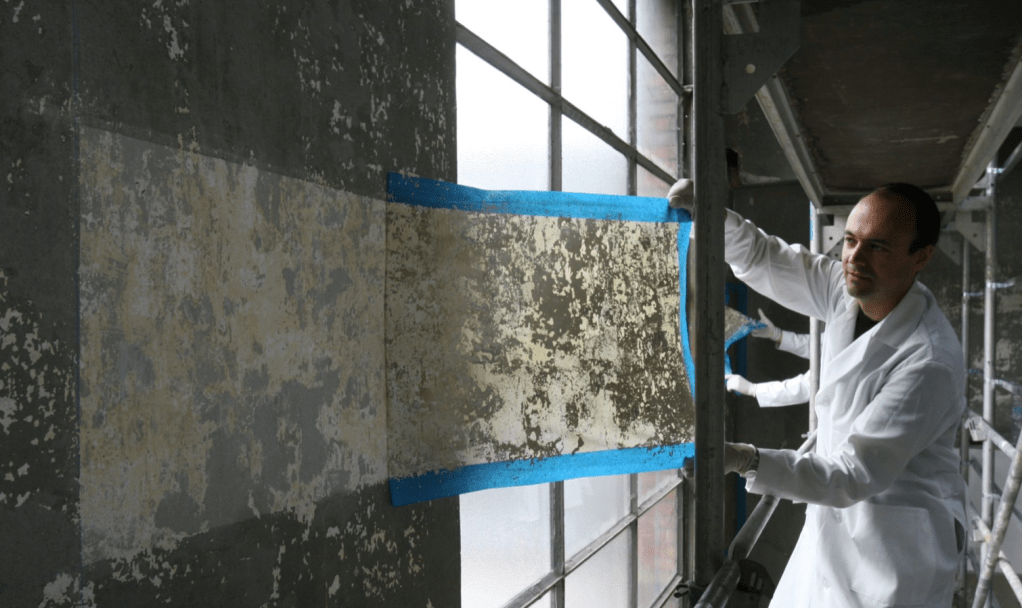

Back in the summer of 2016, I was fortunate enough to pay a visit to Westminster Hall at the Palace of Westminster (a UNESCO world heritage site) to see The Ethics of Dust. Commissioned and produced by Artangel, the exhibition by architectural preservation expert, turned artist – Jorge Otero-Pailos consisted of a 50-meter long and 6–meter high latex cast of the east wall, manifested from a restoration process designed to remove surface pollution from the walls of the hall itself. By spraying and then gently peeling off latex, Otero-Pailos had given the Hall a kind of ‘chemical peel’. And, like all such cosmetic procedures, it had become renewed through an intensive cleanse – lifting over 900 years of accumulated dirt, dust, soot, and grime from the limestone wall. The resulting cast, embedded with this dirt, once suspended from the roof adjacent to the east wall, exudes an ethereal radiance, when backlit from strategically positioned spotlights

The Ethics of Dust suggests a subtle interplay between permanence and impermanence, absence and presence, and elements of the solid/fragile. These are qualities that could be said to characterise many heritage sites, but are made elegantly visible through Otero-Pailos’s site-based intervention of this relict imprint. The latex cast at first glance, appears solid. Yet this illusory perception is ruptured as the whole assemblage sways gently in a breeze blowing in from the entrance hall, and a distinct latex smell reminds us that this is not stone but a far more fragile and ephemeral substance. The waxen colour, the folds and creases in the cast, evoke ancient parchment. Like a hanging map, I find myself cognitively attempting to ‘decode’ the cast, trying to spot identifying features to match it to the original wall as I walk its length. This act, combined perhaps with the adoption of the focused vision of those tasked with this preservation project, reveals small details that otherwise may have remained overlooked: fine hairline cracks , pitted and patinated surfaces, and differently sized limestone blocks. Simultaneously this new conceptual wall also evokes shed skins, or the shrouds used to wrap and encase the recently deceased, or objects intended to remain private or sequestered. Such analogies – of emergence, protection, and way-finding – are especially apt for an artwork which, essentially, is the by- or waste-product of a conservation process used to ensure the future longevity of this heritage site.

Recent examples of digital scanning and 3D printing used in preservation to recreate heritage sites also come to mind when viewing The Ethics of Dust. For example, the replica of the Triumphant Arch from Palmyra (Syria) destroyed by Isis in October 2015, and reconstructed and installed in London’s Trafalgar Square at a later date. Yet Otero-Pailos’s cast was never intended to be an exact replica or a reconstruction, but is something entirely different. By lifting layers of embedded dust from the original wall, I find myself thinking of the palimpsest as the work removes and displays these layers as physical traces of past events and times. By putting the practices and processes of conservation on display, the dust functions as both a substance considered to pose a threat to the future durability of this heritage site, and yet is also re-positioned as heritage in itself. The accompanying catalogue presents the dust as a witness to past events, if not indeed actually produced by,and evidence of these events: ‘Westminster Hall dates back to 1099 and its limestone walls have held the dust, soot and dirt from events including the Great Smog of 1952 and the trials of Guy Fawkes in 1606 and King Charles I in 1649’ we are told. This ephemeral substance is exhibited as holding historic value, and (it is implied) by fixing the dust in latex traces of past events are made at least conceptually tangible.

By conceptualising dust as both a destructive pollutant and constitutive palimpsest trace of heritage, I suggest that this kind of intervention also foregrounds the reluctance to ‘let go’ in the realm of cultural heritage driven by a preference for ‘loss aversion’ . The dirt has been successfully removed. Yet it has not been discarded but exhibited as substance with a combined historical, and artistic value. A substance that, once removed from the stone, is unlikely in contemporary post-Clean Air Act (1956) Britain to return (or at least to the extent of past blackened industrial British cities).

AnMór Studio’s current and ongoing research into the processes of abandonment, erosion, and dereliction and their impact on human memory and objects of remembrance, shows how letting go of things sometimes creates new kinds of profusion – most notably, for example – information and documentation. Catalogue records for objects that are disposed or dispersed from collections are updated with information to document these decisions, record motivations, and provide evidence that appropriate processes were followed and due diligence taken. The dusty cast, like such catalogue records, may be viewed as a remnant or trace of specific heritage decisions and negotiations. A remnant that is retained and held onto, partly perhaps, as a procedure of care. Perhaps this work, by its very nature indicates legitimate alternatives to the demolition or erasure of heritage sites that no are no longer seen to have any cultural worth, yet deserve in some way to be recorded for posterity, and for the benefit of future generations. Recent developments in laser scanning demonstrate the ability and commitment of conservation-led organisations towards digitally preserving historic buildings for historic records in perpetuity, but in the context of his work, Otero-Pailos points the way to a more elegant and enduring methodology that has the ability to not only preserve, but also to create artefacts of enduring beauty that transcend more traditional notions of what constitutes a work of landscape art.

On entering the exhibition a security guard screening my bag rather wryly declared that I was only about to see some ‘dusty old sheets’. Dusty old sheets these may be. Yet sheets (as I hope this dispatch has shown) that I have found beautiful, intriguing, and ultimately provocative for the questions they raise about the processes and practices of cultural heritage.

AN EXPANDED VERSION OF THIS ARTICLE WILL APPEAR IN EDITION 4 OF ECHTRAI JOURNAL , DUE FOR PUBLICATION IN SPRING/ SUMMER 2024